Chapter 3: Cranial Nerves

Author's Commentary

The cranial nerves provide movement, sensation, and autonomic functions for the head and neck:

- They are also the peripheral components of vision, audition, taste, and smell.

- They are frequently involved in both central and peripheral disease processes.

- Their central nuclei are essential to localization within the brain stem.

Cranial Nerve I

Odorants excite olfactory receptors of the sensory cells of the olfactory epithelium. These ciliated cells have central processes that form bundles that are the filaments of the olfactory nerve. Patients are asked to identify various odor ants utilizing a selective nostril. Distorted smell is called parosmia. Olfactory hallucinations occur with medial temporal lobe and uncal lesions. Loss of olfaction is primarily from the bulb, tract, and root lesions.

Cranial Nerve II

Visual loss in one eye is from retinal ganglia cell loss or disease of the optic nerve. If visual loss is bilateral, it is retrochiasmal. At the bedside, confrontational testing is utilized. Color desaturation (red) is a marker of a lesion within the visual system, which may be detected prior to a visual field deficit. Examination of the fundus allows for evaluation of the optic disc, venous pulsations (a measure of intracranial pressure), papilledema, atrophy, and pallor. Blood vessels, the retina, hemorrhages, exudates, tubercles, phakomas, pigmentary alterations, collagen defects, and myelinated nerve fibers are readily apparent.

Cranial Nerves III, IV, and VI

Cranial nerves III, IV, and VI comprise the peripheral components of the oculomotor system. Their nuclei of origin are essential for brain stem localization. Conjugate gaze deficits and nystagmus are major localizing features of central lesions.

General inspection reveals esotropia and exotropia, vertical squints, exophthalmos, enophthalmos, and hypo or hypertelorism.

Inspection of the conjunctiva may demonstrate subconjunctival hemorrhage (head trauma, hypertension), leptospirosis, and other infectious etiologies. Telangiectasia, retroorbital tumors, renal failure, dry eye are all harbingers of specific entities.

The cornea and iris are affected in congenital syndromes, loss of sympathetic innervation, syphilitic infection, and copper deposition (Descemet’s membrane). Collagen vascular disease and several syndromes induce conjunctival ulcers. Eyelid position, ptosis, lid retraction all localize and suggest different disease processes.

Evaluation of the pupil (size, shape, equality, and speed of movement) is important for central lesion localization (IIIrd nerve nuclei, thalamus, pons, medullary Horner’s syndrome). Testing for reaction to light, convergence, and accommodation for near are further tests of pupillary function.

Ocular movement evaluation requires evaluation of eye deviation in primary gaze. Eye muscles are yoked such that the yoked partner will displace the eye in its direction of gaze. Individual extra-ocular muscles displace the globe toward their primary field of gaze.

In the analysis of diplopia:

- The angle of incidence equals the angle of reflectance.

- Separation of the images is greatest in the field of gaze, in which the weak muscle has its purest action

- The false image is displaced furthest in the direction in which the weak muscle moves the eye.

Conjugate eye movement deviation is a strong feature of central lesion localization in conjunction with hemiparesis, posture, and level of consciousness. The cortical center for horizontal gaze is in the frontal lobe, and its counterpart in the brain stem is the paramedian pontine reticular formation. The conjugate center for vertical gaze is in the midbrain at the level of the superior colliculus. Many brain circuits are involved in the oculomotor system’s control of the conjugate gaze.

Nystagmus is caused by an imbalance of tone that is maintained from the retina, eye muscles, vestibular nuclei, and proprioceptive input from the cervical joints and muscles. Nystagmus is helpful in cortical and brain stem localization.

Primary forms of nystagmus are:

- Horizontal (“jerk nystagmus")

- Vertical nystagmus (upbeat nystagmus and downbeat nystagmus)

- Rotary nystagmus

- See-saw nystagmus

- Nystagmus retractorius

- Convergent retraction nystagmus

- Optokinetic nystagmus

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia is seen with lesions that disconnect the IIIrd and VIth nerve nuclei. The medial longitudinal fasciculus is the affected tract. It decussates posteriorly close to the paramedian pontine reticular formation. Accommodation is mediated by anterior fibers that also innervate the IIIrd nerve nucleus.

Cranial Nerve V

The Vth nerve is comprised of a motor, sensory, and three associated nuclei: the rostral, interpolaris, and caudal nuclei. It has variable innervations. There may be a loss of sensation of the entire distribution of the three divisions, or each division in an isolated fashion. It innervates the muscles of mastication.

Cranial Nerve VII

The seventh cranial nerve and the nervus intermedius are anatomically approximate. The seventh nerve has a long course; the location of lesions is often dependent on its associated neurologic deficits. The seventh nerve has a long course; the location of lesions is often dependent on its associated neurologic deficits.

The adjacent nervus intermedius innervates:

- The lacrimal gland via the superficial petrosal nerve

- The salivary glands through the chorda tympani (taste for the anterior 2/3 of the tongue)

- The upper facial muscles bilaterally (area 4)

The seventh nerve nucleus (lower 1/3 of the pons) receives input from the contralateral basal ganglia, thalamus, and the temporal lobe.

This innervation and its projection to the frontal lobe constitute the mimetic or emotional facial. Upper motor neuron lesions cause paralysis of lower facial musculature contralaterally while lower motor neuron lesions paralyze the entire facial musculature ipsilaterally.

Cranial Nerve VIII

The eighth cranial nerve transmits impulses from the depolarization of the hair cells of the organ of corti in the cochlea to the spiral ganglia.

It has a complicated intracranial course that entails synapses in:

- The dorsal and ventral cochlear nuclei (medulla)

- The trapezoid body (pons)

- Lateral lemniscus (midbrain)

- Medial geniculate body (thalamus)

- Heschl’s gyrus of the temporal lobe.

- It contains ipsilateral uncrossed fibers as well as crossing fibers at many levels.

Associated neurologic deficits determine the localization of lesions. Central lesions rarely cause deafness, the exception being compression of the collicular plate. Unilateral deafness is always of peripheral origin. In general, middle ear pathology causes the loss of low tones, while nerve deafness decreases the high tones.

The origins of the vestibular portion of the VIIIth nerve are the ampullae of the semicircular canals and the otoliths of the sacculus and utriculus. Their displacement by endolymph with head movement depolarizes mechanoreceptors. The nerve projects to the vestibular ganglia and then synapses in the vestibular nuclei of the medulla. Its connections are widespread throughout the CNS. Disturbances of vestibular function cause falling, past pointing, vertigo, and nystagmus.

Cranial Nerves IX and X

The primary functions of the IXth and Xth nerves are:

- Somatic sensation from the pharynx, larynx, tonsils, soft palate and posterior 1/3 of the tongue

- Taste from the posterior 1/3 of the tongue (primarily IX)

- Motor innervation of the palate and pharyngeal musculature

- Motor innervation of the vocal cords (Xth nerve)

- Cardiovascular, respiratory and gastrointestinal reflexes (IXth and Xth nerves)

- The external esophageal sphincter (cricopharyngeus muscle – IXth nerve).

Cranial Nerve XI

The spinal component of XI primarily innervates the upper components of the trapezius muscle and sternocleidomastoid muscles. At rest, a forward flexed head supports trapezius weakness.

Sternocleidomastoid weakness is associated with a head that is falling backward. This musculature is essential for head movement control.

Cranial Nerve XII

The hypoglossal nerve is purely motor and controls all movements of the tongue

Excerpts From Chapter 3

First Cranial Nerve

Very few things happen to the olfactory nerve (first). It should be tested carefully in head injury (where it is ripped from the cribriform plate), extra-parenchymal tumors of the base of the frontal lobe (meningioma of the olfactory groove) or intrinsic tumors of the nasal epithelium (neuroesthesioblastoma), vitamin B12 deficiency, Kallmann’s syndrome (ovarian dysgenesis) and neurodegenerative disorders such as multiple system atrophy and Parkinson’s disease.

Anatomy

Odorants excite neurons of the nasal mucosa, which project to the olfactory bulb, tract and roots (primarily the lateral root), which in turn project to the periamygdaloid and prepiriform cortex of the temporal lobe which then projects to the uncus and hippocarpal gyrus. Loss of olfactory sensation occurs primarily with bulb, tract and root lesions, while olfactory hallucinations occur with medial temporal and uncal lesions. These are usually described as unpleasant smells such as burning rubber, rotten food or undesirable bad smells. Approximately 10% of reported smells are good, but usually are described as “too sweet." Olfactory auras are dramatically important in the diagnosis of medial temporal lobe epilepsy. Inferior frontal lobe gliomas may also present with bilateral anosmia.

Method of Testing

Small bottles of coffee, almonds, chocolate and peppermint can be used. The test odor is placed under one nostril while the other is compressed. New scratch smell tests are now available. The patient is required to identify the odors. Patients who describe the odors as the same, but distorted and unpleasant, have paraosmia, often noted with Hencken’s syndrome. This is a postviral phenomenon in which the nasal mucosa and the olfactory mucosa have been damaged. Paraosmia may occur because of incomplete olfactory recovery following head injury. Schizophrenia, depression, and hysterical conversion syndromes have been described with these symptoms. Rarely, patients with sarcoid, paraneoplastic syndromes, chronic meningitis and siderosis (iron deposition from recurrent intracranial bleeding) present with anosmia.

Examination Technique Demonstration

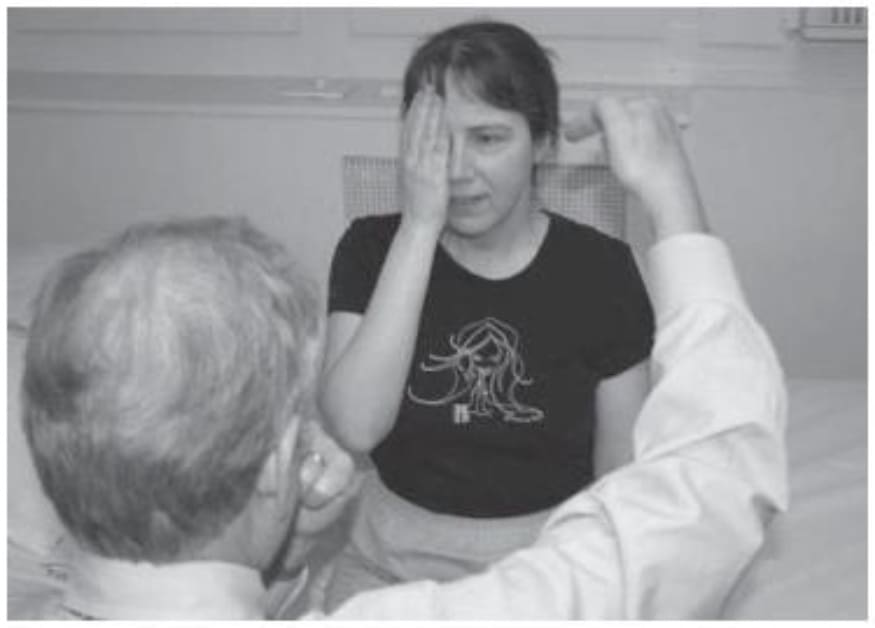

Fig. 3.1 (a) Monocular confrontation visual field testing. The patient is asked when the finger can be seen and when it has an flesh color to it (macular vision). (b) The patient is asked which hand is brighter and which hand moves when they are moved simultaneously. The examiner also notes gaze preferences.

Fig. 3.1 (a)