Chapter 6: Involuntary Movements

Author's Commentary

Involuntary movements are generated from circuitry that entails almost all parts of the neuraxis. Specific movements define various circuitries for the level at which they are generated.

Excerpts From Chapter 6

In evaluating the patient's involuntary movements, the examiner must discern the following:

- What part(s) of the body are affected?

- Is it constant or intermittent?

- Is it present at rest, intention, or both?

- Does voluntary movement increase or suppress it?

- Is it altered by any position of the limbs or trunk?

- Is it affected by the environment, temperature, or the patient’s emotional state?

- Is it suppressed or exaggerated by visual input?

- Occurrence during sleep?

- Is the patient conscious of it, and, if so, can they suppress it?

A great deal of the examination occurs while the history is taken. The examiner should note the position of the patient in the chair. Patients with cerebellar disease, particularly the vermis, utilize the back of the chair for support. Basal ganglia disease patients are rigid and forward flexed. The choreoathetotic movements of Huntington’s disease and peak-dose dyskinesias of dopaminergic therapy in Parkinson’s disease are evident. A side-to-side head tremor suggests essential tremor, an up-and-down oscillation of the head, a third ventricular tumor in a child, or basal ganglia disease in an adult. A dropped and plantar flexed foot, suggests the dystonia of chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS) or a primary dystonia. Tremor at rest indicates Parkinson’s disease. Generalized rigidity, stiff person’s syndrome, an akinetic rigid syndrome (multiple system atrophy (MSA), corticobasal ganglionic degeneration, frontal temporal degeneration (FTD)-chromosome 17 parkinsonism), tics and vocalizations, with abnormal movements suggest Tourette’s disease and startle myoclonus (myriachit, the “jumping Frenchmen" of Quebec). There is a genetic deficit of glycine, an inhibitory spinal cord neurotransmitter.

There is no other aspect of neurology that requires as good a clinical examination as that for involuntary movement. The good examiner trumps all imaging devices in most instances within 2–3 seconds. There is no magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) abnormality in most patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Movements Limited to Muscles

- Fasciculation

- Fibrillation

Examination Technique Demonstration

Fig. 2.3

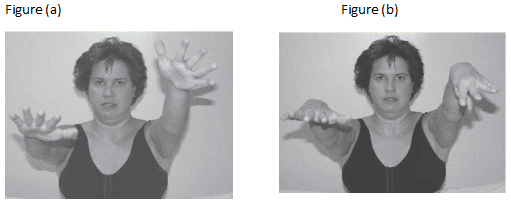

Fig. 6.3 Finger wandering/updrifts. Finger-playing is a movement of the hand without proprioception. Often, injury to the dorsal root ganglia. (a) Parietal updrift. The hand drifts up and out, with or without sinuous movements of the finger.

(b) Thalamic updrift. The wrist flexes with the thumb adducting into the middle palm.